State Of Emergency Florida Coronavirus

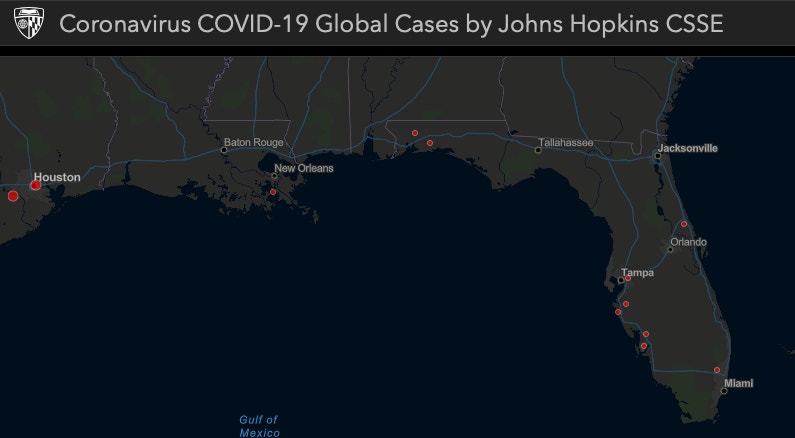

© Provided by Live ScienceA sunset at Naples Beach Florida.Last updated April 22 at 4:47 pm ETThere are 28,309 people who have tested positive for COVID-19 in Florida,. This makes Florida 8th in the list of states with the most cases.Of those people, 1,636 have traveled, 8,142 have had contact with a confirmed case, 1,384 have traveled and had contact with a confirmed case and 16,381 are under investigation. There are now 893 people in Florida that have died from COVID-19, according to the.Governor Ron DeSantis issued a stay-at-home order for the entire state starting on Thursday (April 2) at midnight. Last week, DeSantis gave permission for some beaches to reopen. Jacksonville Mayor Lenny Curry reopened beaches with restricted hours and people flocked to them.

(AP) — Swift-moving developments over the new coronavirus ricocheted across Florida's Capitol as Gov. Ron DeSantis declared a state of. Coronavirus: In-Person Events of 50 or More Should Be Canceled for. County, Florida, officials as they declared a local state of emergency.

Photos of groups of people on the beach drew criticism on social media.DeSantis had declared a State of Emergency for COVID-19 in Florida on March 9.Florida has set up a hotline for coronavirus information: 1-866-779-6121.

Who lives, and who dies, if coronavirus patients overwhelm hospitals and force doctors to ration beds, ventilators and care?It’s a distressing but vital question to ask during a pandemic. In Florida, however, it’s one health officials wouldn’t answer.State officials have punted this ethical dilemma to health care providers, who in response have filled the void with a patchwork of protocols as Florida nears its peak period of hospitalizations for COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. Experts say standardized, ethical guidelines for rationing care is crucial in a crisis when there is a scarcity of medical supplies. Without them, patients could be discriminated against or receive unequal care, and it opens the door to legal liability for health care providers.

At the same time, not having such protocols could put extra pressure on doctors, nurses and emergency responders, many of whom are already at their breaking points.' No one wants to make that call. It’s heart-wrenching,” said Sara Singer, a Stanford University professor who studies hospital safety and health care policy. “So you need to have their backs.”.

“The Department of Health is following the latest (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) guidance, which focuses on Personal Protective Equipment alternative strategies, resource allocation and conservation,” health department spokesman Alberto Moscoso said in the statement. “The Department maintains regular contact with health care providers across the state to ensure they are receiving the medical equipment and resources needed to continue testing and treating patients for COVID-19.”The state’s lack of guidance concerns Tony DePalma, director of public policy with Disability Rights Florida.

LEGO Set G577-1 Vikings Chess Set - building instructions and parts inventory. LEGO Set G577-1 Vikings Chess Set - building instructions and parts list We are aware of an issue with sending emails, and are investigating.  This exclusive LEGO Vikings Chess set includes a total of 32 chess pieces, featuring 24 minifigures. Just choose your color and you're ready to begin!. One-piece chess board measures 10' x 10' (25.4 x 25.4 cm). This exclusive LEGO Vikings Chess set includes a total of 32 chess pieces, featuring 24 minifigures. Just choose your color and you're ready to begin! One-piece chess board measures 10 x 10 (25.4 x 25.4 cm). The LEGO Vikings (Series: Chess) is a set containing parts & pieces. It gives not only children, but also adult fans and collectors, the opportunity to entertain themselves and let their creativity and imagination run wild.

This exclusive LEGO Vikings Chess set includes a total of 32 chess pieces, featuring 24 minifigures. Just choose your color and you're ready to begin!. One-piece chess board measures 10' x 10' (25.4 x 25.4 cm). This exclusive LEGO Vikings Chess set includes a total of 32 chess pieces, featuring 24 minifigures. Just choose your color and you're ready to begin! One-piece chess board measures 10 x 10 (25.4 x 25.4 cm). The LEGO Vikings (Series: Chess) is a set containing parts & pieces. It gives not only children, but also adult fans and collectors, the opportunity to entertain themselves and let their creativity and imagination run wild.

His organization to Gov. Ron DeSantis last month, asking that his administration ensure “non-discriminatory access' to medical care for people with disabilities during the COVID-19 emergency. The administration has not responded.“It’s dangerous that the state is trotting up to this moment without clearly indicating that federal anti-discrimination laws are in place and that care will be coordinated as such,” DePalma said. Related:To fill the vacuum, the Florida Bioethics Network has produced itsMade up of large institutional members such as Baptist Health South Florida, Cleveland Clinic, UM Health and Jackson Health, as well as a few hundred individual members, the network aims to resolve ethical and legal problems involving health care and research. It pointed to the possibility that there will be a shortage of ventilators during the coronavirus pandemic. Failure by the government and institutions to prepare, it warned, “invites disorder, permits arbitrariness, risks bias and increases the likelihood that patients who would have survived with ventilator support will die because patients likely to die were using the machines.”“The failure to adopt some sort of guidelines like this will lead to more people dying,” said Dr. Kenneth Goodman, director of the Florida Bioethics Network.

“Why would anyone want that?”The group’s guidelines say decisions should be made regardless of a patient’s social status or demographics. It proposes to score patients based on levels of organ failure and other underlying health issues, including dementia, metastatic cancer or end-stage renal disease. The guidelines suggest using age only as a tiebreaker, giving younger patients priority. A COVID-19 patient receives support from a ventilator in a negative pressure room (NPR) recently at Gulf Coast Medical Center in Fort Myers, Florida.

NPRs help prevent cross-contamination from room to room. The room's ventilation system generates pressure lower than of the surroundings, allowing air to flow in but not out. @2020 KINFAY MOROTI/SPECIAL TO TAMPA BAY TIMES Kinfay MorotiWithout uniform guidelines across the state, someone at one hospital might be denied a ventilator that would have been given to them at another hospital.

That could lead to “lawsuits and a setting for recrimination and criticism,” said Richard Hopkins, Florida’s acting state epidemiologist until he left in 2012.Many states realized the need for preparedness plans and crisis standards of care after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, said Nancy Berlinger, researcher at the Hastings Center, a leader in the field of bioethics.Now, some states are rapidly updating that work to fit with the unique challenges related to COVID-19.The general principles of crisis standards of care are fairly straightforward: prioritize to save as many lives as possible. But how exactly that’s determined differs, and is fraught with ethical questions.

Earlier this year, Alabama made for a that said in part people with “severe mental retardation. May be poor candidates for ventilator support.” (Alabama later withdrew those guidelines.)On March 28, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Civil Rights issued a reminding states that civil rights protections are not waived in an emergency.Florida is not the only state that hasn’t addressed this issue. A recent, a nonprofit newsroom, found 20 other states do not have (or would not provide) emergency triage guidelines. Some states, including Arkansas, Delaware, Idaho, New Jersey, Virginia and Massachusetts, are scrambling to put together policies now. And others, like California, have vague protocols of little help to front-line workers, or include policies that advocates say discriminate against people with disabilities, the report said.In Florida, Hopkins said he once urged officials to hold workshops across the state.

He wanted to bring together residents, faith leaders and medical experts to build public support for this sensitive issue. The idea went nowhere.As Hopkins put it: 'I was a voice in the wilderness.”The Department of Health has taken up this ethical dilemma in the past, only to shelve the final outcome without adopting it. In 2011, the Department of Health drafted procedures that sounded especially helpful for the current crisis: “” It was a 41-page map that could navigate doctors through the most difficult life or death decisions.The goal of the guidelines, the document said, was to “provide the greatest good for the greatest number,” and “reduce or eliminate healthcare worker liability.”The guidelines were never adopted. While it’s unclear why, the issue did come up soon after “death panels” emerged as an unfounded boogeyman that haunted the 2010 passage of the Affordable Care Act. A Department of Health spokesman refused to comment.Asked about the state’s triage guidelines, Mary Mayhew, the secretary for the Agency for Health Care Administration overseeing hospitals, said: “I’m not sure what you mean in terms of triage.” Pressed further, she added: “I can’t speak to that from my agency’s perspective,” and directed questions to the Department of Health.Goodman, who worked on the 2011 guidelines, said he didn’t know why the effort was abandoned. He said the Florida Bioethics Network’s guidelines were partly derived from it.As the Times reported this story, the Department of Health removed the 9-year-old draft document from its website.